Previously, I described how audio signals can sum together and produce various results depending on frequency, amplitude and phase. We’ve seen that these rules apply in any realm — digital, analog, or acoustic — as long as the medium is linear.

This is pretty much the end of the story for the digital and analog realms, where the signal can simply be represented as a variation of amplitude over time, i.e. a single waveform. The acoustic realm, on the other hand, doesn’t just have a time dimension, it has spatial dimensions as well. So far, when discussing wave summation and interference we’ve been ignoring these spatial dimensions, instead focusing on sound pressure at a single point in space only. Just like the previous post focused on how distance in space can affect the amplitude of a signal, it seems appropriate to discuss the concepts of summation and interference in a spatial context.

In this post we’ll look at the interaction between two spatially separated sound sources that, for the sake of simplicity, are both radiating the same 250 Hz sine wave. We’ll use a 2D projection because 3D space doesn’t matter too much for this post and it makes things easier to visualize. Furthermore, just like in the previous post, we’re going keep things clear and focused by assuming free field conditions, i.e. sound propagates unimpeded without meeting any obstacles such as walls.

Two sources, one listener

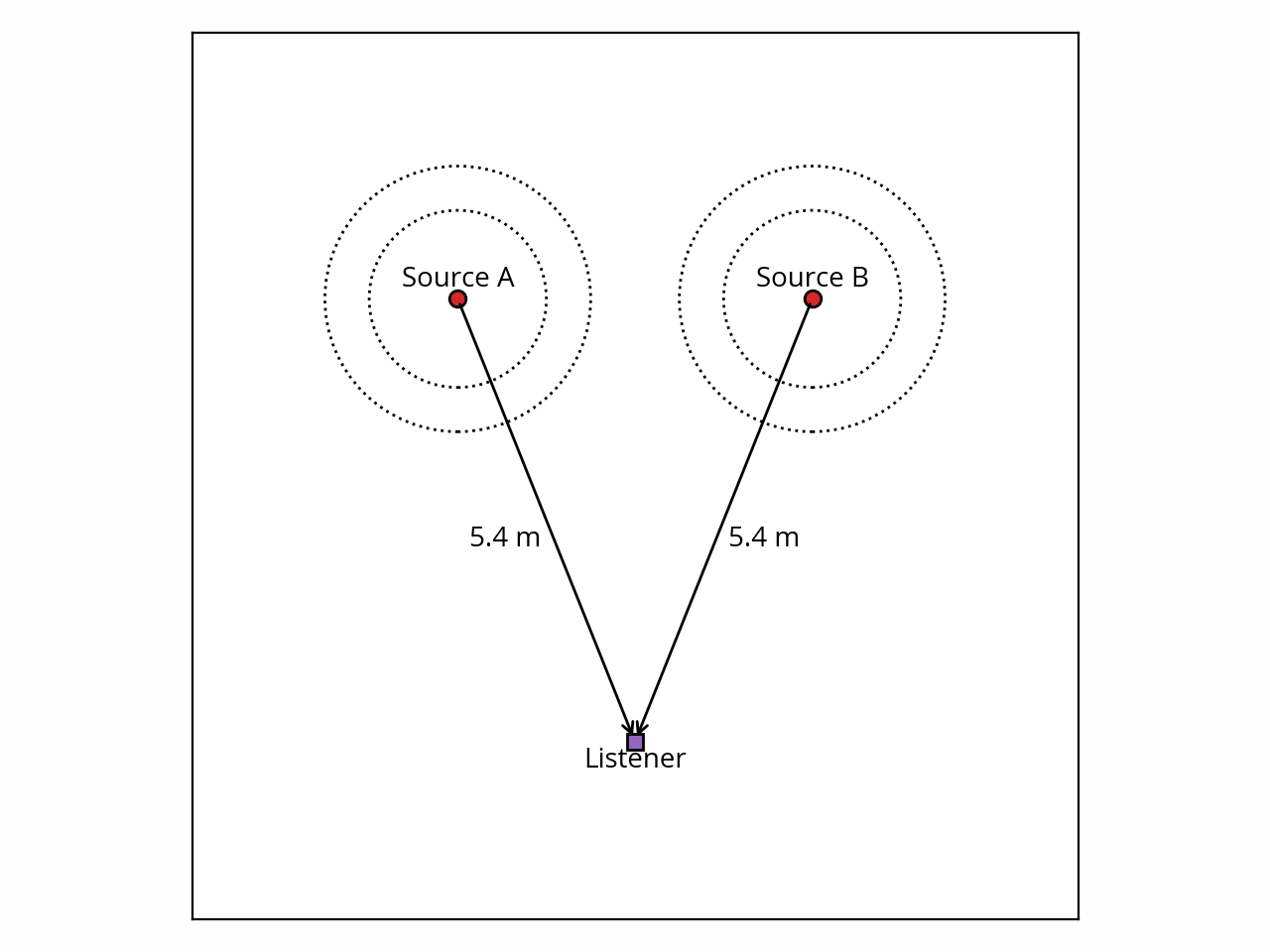

Let’s set the stage as, say, a 10-meter square area with some arbitrary reference listening position equidistant from both sources. Something like this:

As one might expect, the sound from sources A and B is going to sum at the listening position. To understand what’s going to happen there, we can refer back to the summation rules we’ve discussed in a previous post. Since the two initial waves are sine waves, we know the result is going to be a sine wave too, and the resulting amplitude and phase will depend on the amplitude and phase of the two waves.

So what is the amplitude and phase of the two constituent waves? Well, for starters, it depends on the characteristics of the sources. For the sake of simplicity we could assume the two sources are identical; for example they could be two closely-matched units of the same loudspeaker model. In fact, we’re going to go one step further and assume that the sources are not only identical but are also monopoles, i.e. they radiate sound in the same way in all directions. This way we don’t have to worry about changes in amplitude and phase depending on the angle at which the listener is facing the source. In a real-world situation we wouldn’t be able to get away with these assumptions, but they don’t really affect the basic principles described in this post; they just make it easier to calculate the results.

Now that the source characteristics are out of the way, we have to consider what happens between the sources and the listener. Here the situation is simple — since the two waves are propagating through the same medium and the listener is sitting at equal distance from both sources, there is no reason to believe their relative amplitude and phase would be affected.

From there we can deduce that both waves will arrive at the listener with the same amplitude and phase, and we can apply the appropriate rule to conclude that the two waves are going to interfere constructively at the listening position.

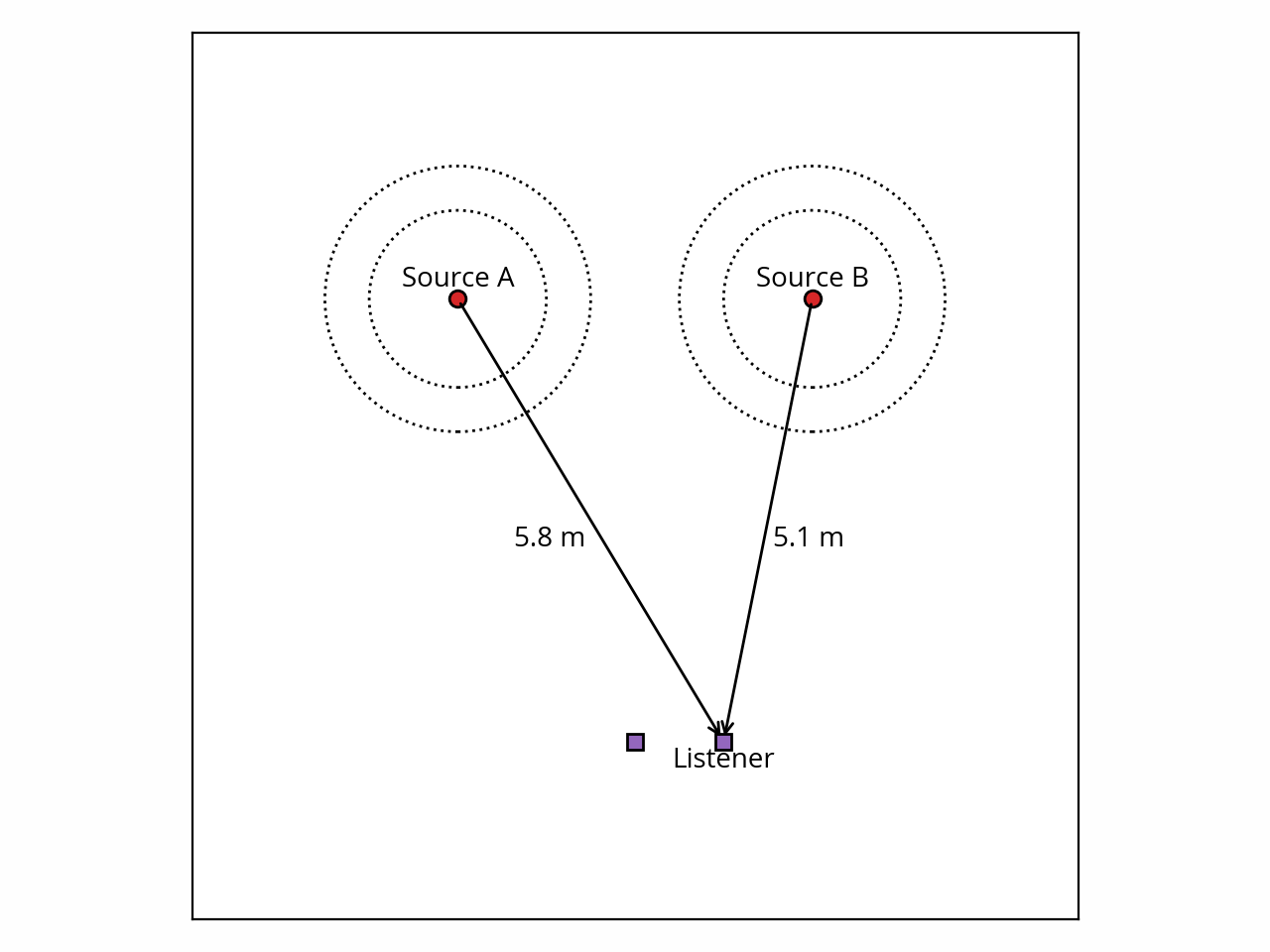

So far so good. What if we move the listener to the side?

In that case the listener is not sitting at equal distance from A and B anymore. This has two immediate consequences. First, due to the inverse square law, the wave from B will have higher amplitude than the wave from A at the listening position. However, because the distances are still somewhat similar in this example, the difference is benign — a mere ~1 dB. For this reason, we’re going to ignore this effect for now.

More importantly, we should point out that the speed of sound is not infinite, which means sound from B will arrive earlier than sound from A at the listening position. In the conditions of a typical room, air travels at around 343 m/s. In our example, sound from A has to travel an additional 0.7 m, which means it will arrive around 2 milliseconds late.

Now, such a small delay might seem inconsequential at first, but consider this: 2 ms is exactly half the period of the 250 Hz sine wave we’re using in our example. Which means that when the wave from A arrives at the listening position, its phase is exactly opposite (180°) relative to the wave from B. If we look at the summation rules for this scenario, we deduce that destructive interference will occur, and since the amplitudes of the two waves are (almost) the same, we can conclude that there is no sound at the listening position!

Interference patterns

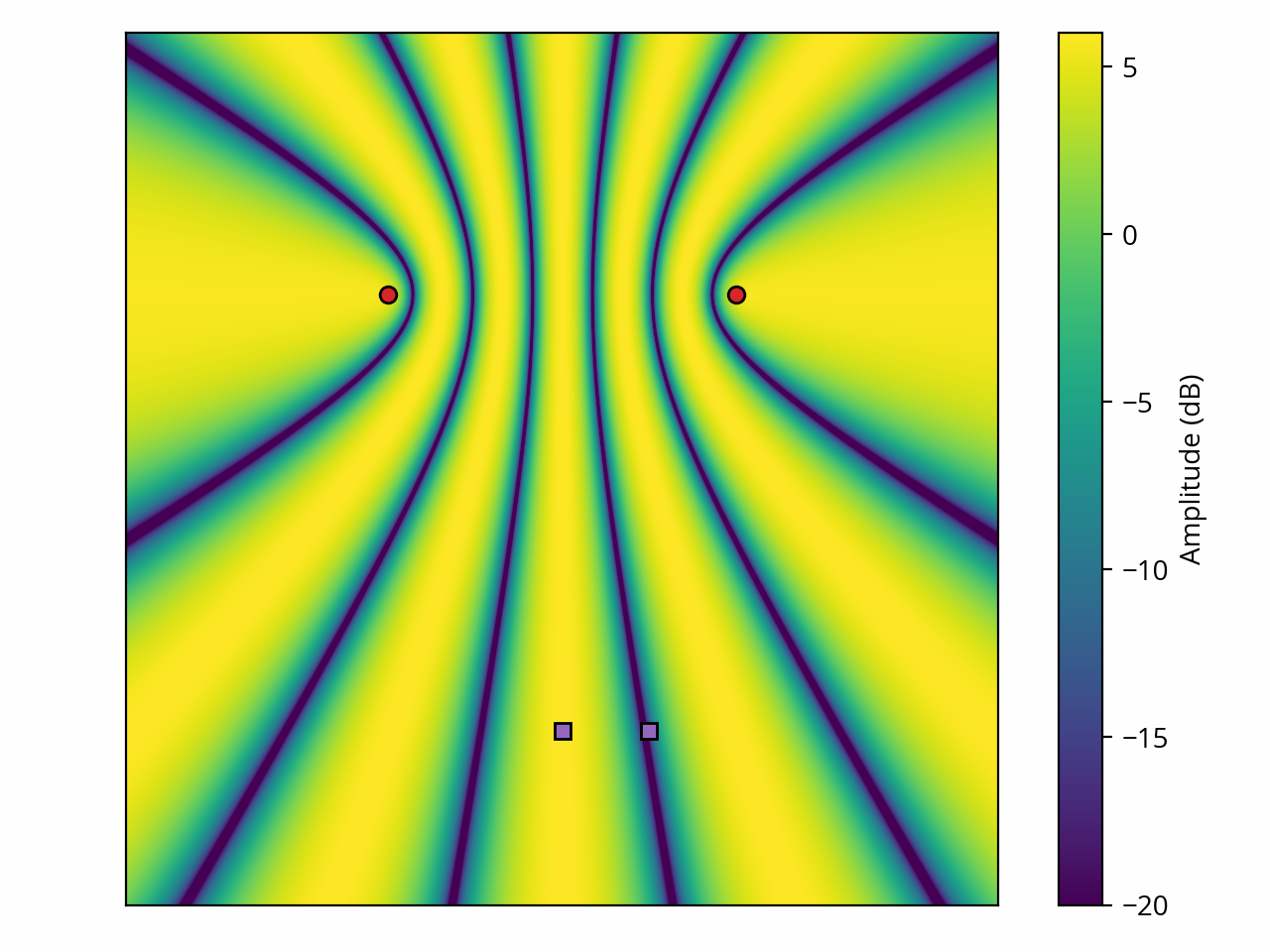

One observation that we can make at this point is that the nature of the interference depends on the difference in propagation delays between the two waves (path difference). if the delay is negligible compared to the period, or if it’s close to an integer multiple of the period, we get constructive interference; at the other extreme, if it falls in the middle, we get destructive interference. We’ve also seen that, in space, due to the speed of sound, delay and distance are intricately linked. Thus our two example sources interact to create interference patterns where sound amplitude and phase varies wildly from one point in space to the next. In other words, we have a complex sound field that shows patterns of constructive and destructive interference:

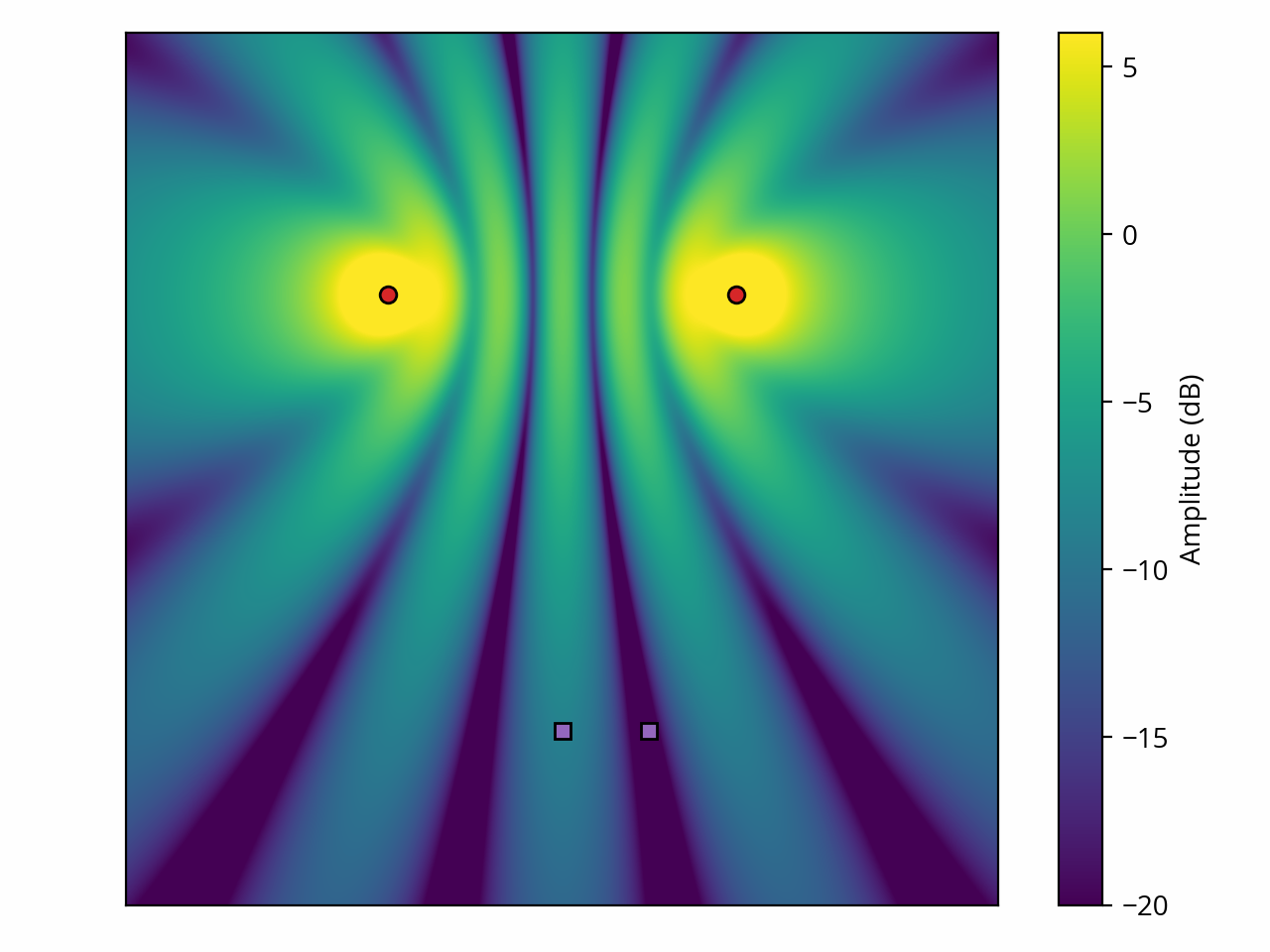

The above plot assumes each of the two sources individually produces 0 dB at every point in space and ignores the inverse square law. If we instead assume that each source can produce 0 dB at a distance of 1 m and apply the inverse square law, we get a more realistic result:

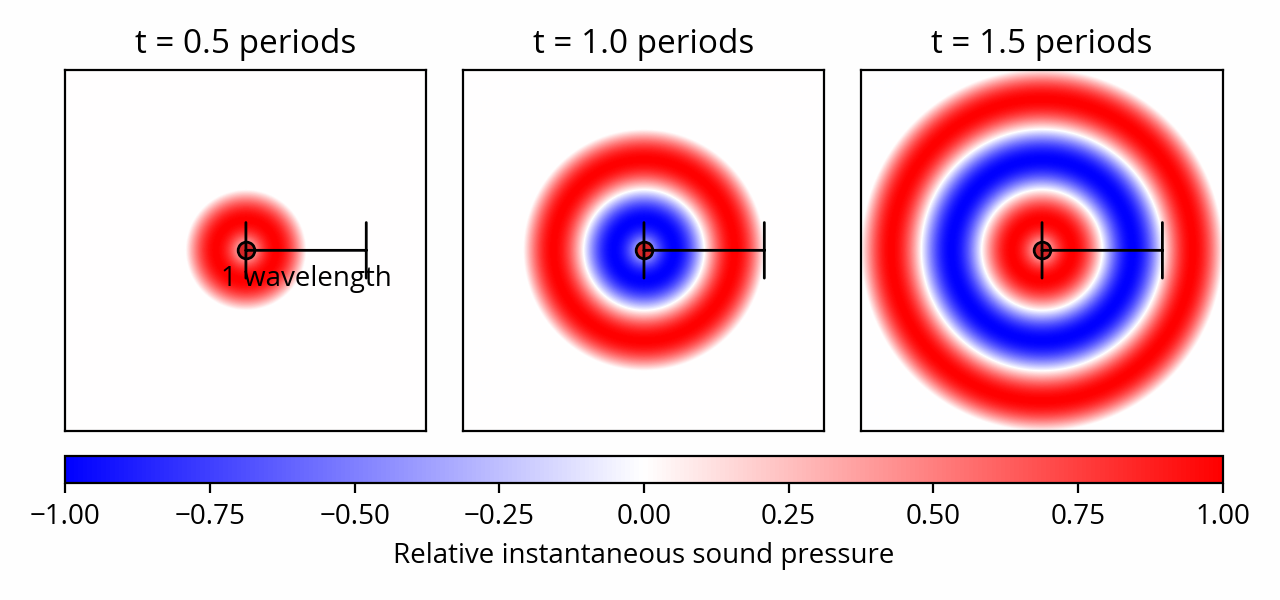

We can also look at this phenomenon from the perspective of wave propagation by examining the evolution of local sound pressure over time. Paul Falstad’s excellent simulator can be used to do just that.

Transient sound field

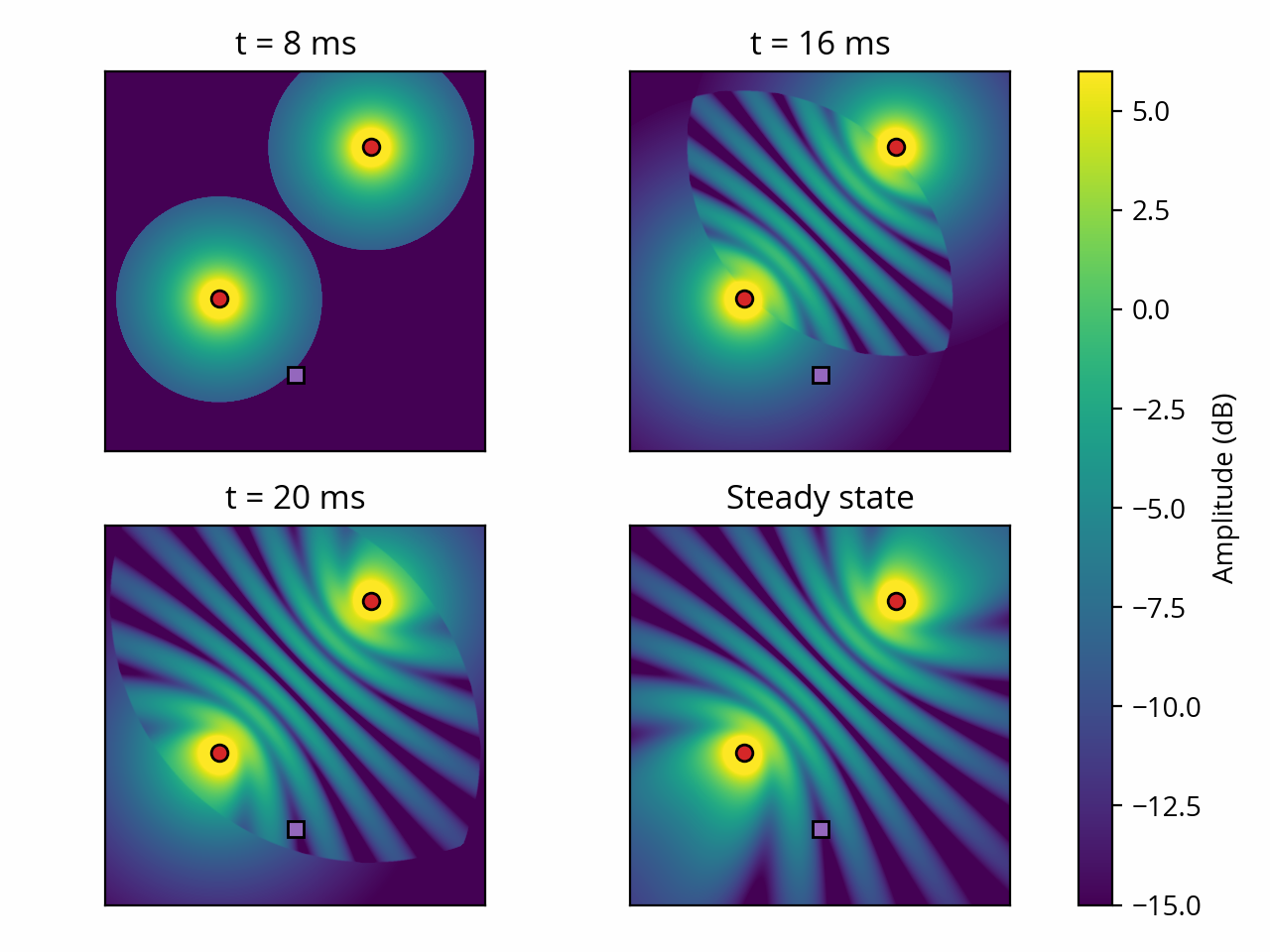

In the example above, we’ve determined that interference occurs because the sound from one of the sources arrives 2 milliseconds later than the sound from the other source. I then showed the resulting sound field after the sound from both sources has traversed the whole area, and the sound field has stabilized: this is called the steady state. This begs the question: what about the transient state, i.e. the window of time just before the sound from the second source arrives at the listener?

In the post where we discussed wave summation, I carefully avoided that question by assuming that the waves were continuous; that is, they have no beginning and no end. Let’s depart from that assumption for a moment and assume that our sound wave has a well-defined start time: our initial condition is that the sound field is completely silent, and our two ideal 250 Hz sine wave sources are switched on simultaneously at t = 0. To make things more obvious, I also rearranged the sources to increase the path difference:

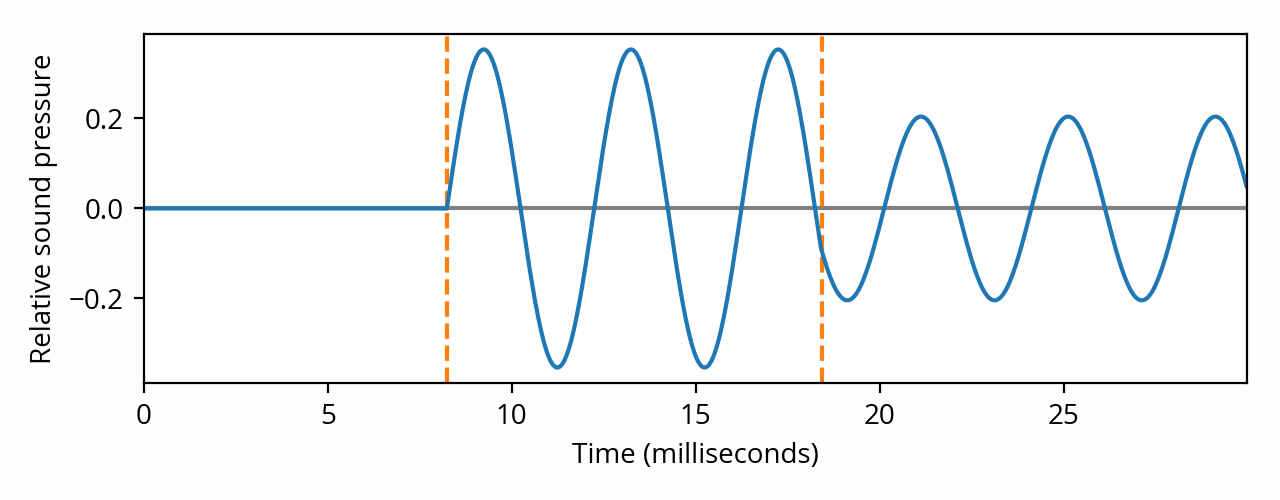

Initially, the listener is not hearing anything because the sound from the first source has not reached it yet. At around 8 ms, the sound from the first source has arrived and the listener starts hearing a wave of about -9 dB amplitude. At around 18 ms, the sound from the second source arrives, interferes with the sound from the first source, and the sound level at the listening position drops to about -14 dB. Shown differently, this is the sound that reaches the listener:

If our listener was a microphone, the above shows the waveform that it would capture. But in the real world we don’t look at sounds — we hear them. This immediately raises a number of very important questions. What if the listener is not a microphone but a human being? What would they hear in this scenario? Would they notice the transient state at all? Would they hear a difference if we only used a single source of similar steady-state amplitude?

These questions are not about physics anymore — they’re about perception. In other words, we are stepping into the field of psychoacoustics. The answers to these questions depend on many factors, such as frequency, transient state duration, and relative amplitude. They also depend on the shape of the signal: if, in our example, we used a very short, impulse-like signal instead of a sine wave, then the sound from the first source would have ended before the sound from the second source reaches the listener. In such a scenario there is no interference at all, the listener hears the same signal twice, and there is no steady state to speak of! As if that wasn’t enough, perception is also affected by the angle at which sound arrives at the listener. [ref] Toole, Floyd E., Sound Reproduction: Loudspeakers and Rooms, chapter 7. [end ref] Needless to say, this is a vast topic to which we will come back in more detail in future posts.

Caution: When making your own acoustical measurements using a microphone and an analyzer, you should always keep in mind that, by default, most of the results that are displayed (in particular the frequency response) are only valid for the steady state. For this reason you should exercise extreme caution when interpreting these measurements and drawing conclusions from them with regard to how the system will sound like to a human listener. This can be quite misleading, especially at high frequencies, and especially if the system under test has long transient states (such as a room, where sound travels distances measured in meters). More details in later posts.

The wavelength

I mentioned above that, in the acoustic realm, delay (or duration) and distance are two sides of the same coin: distance differences cause delay differences which, relative to the period of the wave, cause interference patterns. We can simplify this story by sidestepping the concept of delay entirely; instead, we could choose to only deal with distances.

In order to do that, we need to convert the wave period, which is a duration, into a distance. Using the speed of sound, we can compute the distance that sound travels in the duration of one period; this is called the spatial period, or more commonly, the wavelength. The formula is very straightforward: the wavelength is the period multiplied by speed of sound (or speed of sound divided by frequency). As usual, calculators are available.

Using the wavelength, we can rephrase the interference phenomena described in the previous section purely in terms of distances. For example, we can say that if the distance difference between the listener and the two sources is close to an integer multiple of the wavelength, then constructive interference will occur. Furthermore, the wavelength of a 250 Hz wave is ~1.4 m, which explains why, in our initial example, destructive interference occurs when the distance difference approaches half that wavelength (0.7 m).

Distance between sources

We’ve observed above that sound from two spatially separated sources can combine to form an alternating constructive and destructive interference pattern. This is true for the specific example that I’ve chosen, but things do not necessarily turn out that way in the general case. Indeed the sound field might adopt a different shape if any of our initial assumptions (i.e. identical, monopole sources) are broken.

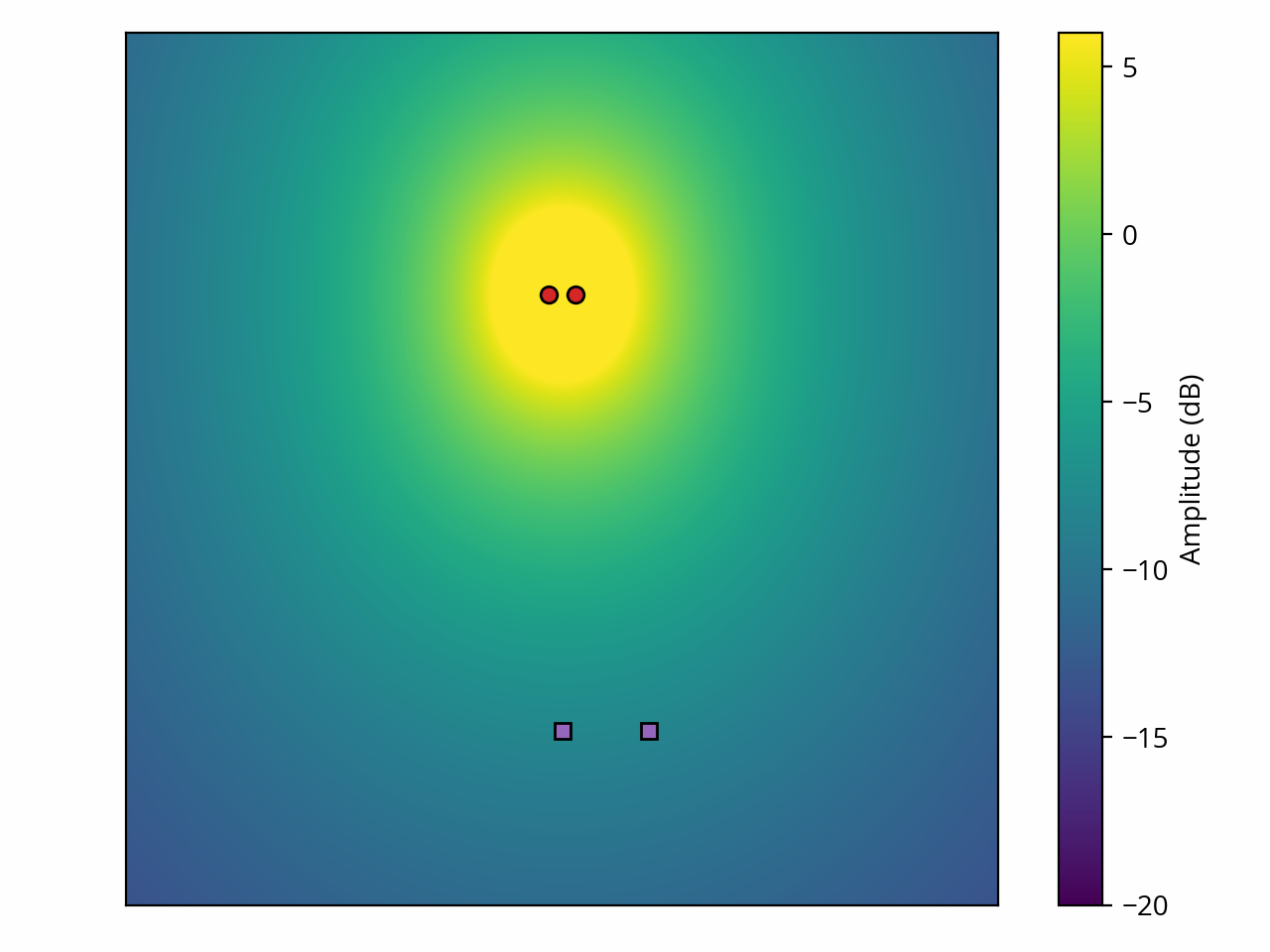

More interestingly, the distance between our two sources also matters. Remember that this particular interference pattern is inherently caused by the path difference between the sources and the listener — if the path difference approaches half a wavelength, destructive interference occurs. Consider this: basic geometry tells us that the path difference cannot be more than the distance between the sources themselves. [note] This maximum is reached if the listener sits on the line that goes through both sources, such that one source lies behind the other from the perspective of the listener. [end note] If that distance is less than a quarter of a wavelength, then destructive interference simply cannot occur anywhere in space, and we are left with only constructive interference:

From this we can conclude that interference patterns tend to disappear if the sources are moved closer to each other. [note] This is why two subwoofers (low frequency, long wavelength) will act just like a single subwoofer with twice the output if they are positioned right next to each other. Things are not that simple at higher frequencies, because the wavelengths are shorter. [end note] Since wavelength is inversely proportional to frequency, lowering the frequency has the same effect.

Caution: Two sound sources can interact in very different ways depending on the wavelengths (frequencies) involved. This is important because the audible range spans a huge range of wavelengths: from 17 meters (20 Hz) down to 17 millimeters (20 kHz). This in turn means that the shape of the sound field can vary wildly depending on which part of the frequency spectrum we are looking at. For this reason it is imperative to clearly state the frequency range of interest when discussing acoustical phenomena in real-world situations — otherwise the discussion makes no sense.