This post will focus on a specific aspect of the acoustic realm: specifically, how the amplitude of a sound wave is altered as it travels through free space. This is useful to gain a better understanding of how loudspeaker systems behave; naturally, it is not as useful when discussing headphones, as in this case there is not much space for sound to propagate into.

To make things easier to understand, I will use a simple unrealistic scenario as a basic starting point. Then, I will elaborate on this scenario so that we get closer and closer to a realistic model of how sound propagates in the real world. Here are our initial assumptions:

- Sound is propagating through a perfect lossless medium. In other words, the medium (in our case, air) opposes no resistance to the passage of sound, and there is no dissipation of sound energy, such as in the form of heat. This is not completely true in practice, and we will revisit this assumption later in this post.

- Sound is coming from a single, small point in space, not from multiple points at the same time. Such a source is called a point source. Perfect point sources don’t exist in the real world, but are a good approximation as long the listener sits in the far field; that is to say, the distance to the source is large compared to the size of the source itself. [note] If we can’t make that assumption, then an alternative is to decompose a complex source into a number of individual point sources, the sound from which sum together at the listening position; this approach is known as the Huygens-Fresnel principle. [end note]

- Sound does not reflect off nearby surfaces. Think of the sound source as levitating in mid-air, with no floor, no walls, no ceiling, basically nothing for sound to bounce off of. This situation is known as free field or free space conditions. Strictly speaking this is implied by the previous assumption, since after all a reflection is itself a sound source — thus the sound would not be coming from a single point anymore.

The latter assumption is of course egregiously wrong when sound propagates in a room, which is the main reason why the scenarios described in this post are somewhat unrealistic. The rules described below should be seen as building blocks to gain a better understanding of how sound propagates through space; they can’t be applied as-is for sound waves propagating through a room where reflections are present. We will tackle that problem in a later post.

Caution: Keep in mind that sound pressure, the metric used to quantify the amplitude of sound in the acoustic realm, refers to pressure variations at a given point in space. It does not refer to some overall amount of sound power that is being radiated away from a source. Local sound pressure depends on where the listener is; in contrast, total sound power is a property of the source only. [note] When a specific sound pressure level is mentioned in the specifications of a sound source (e.g. a loudspeaker), it is always relative to a specific distance from the source (typically 1 meter), at a specific angle (typically on-axis, i.e. 0°), under specific conditions (typically half-space, i.e. with the loudspeaker against a wall). Such a number is valid for this point only. [end note]

One dimension

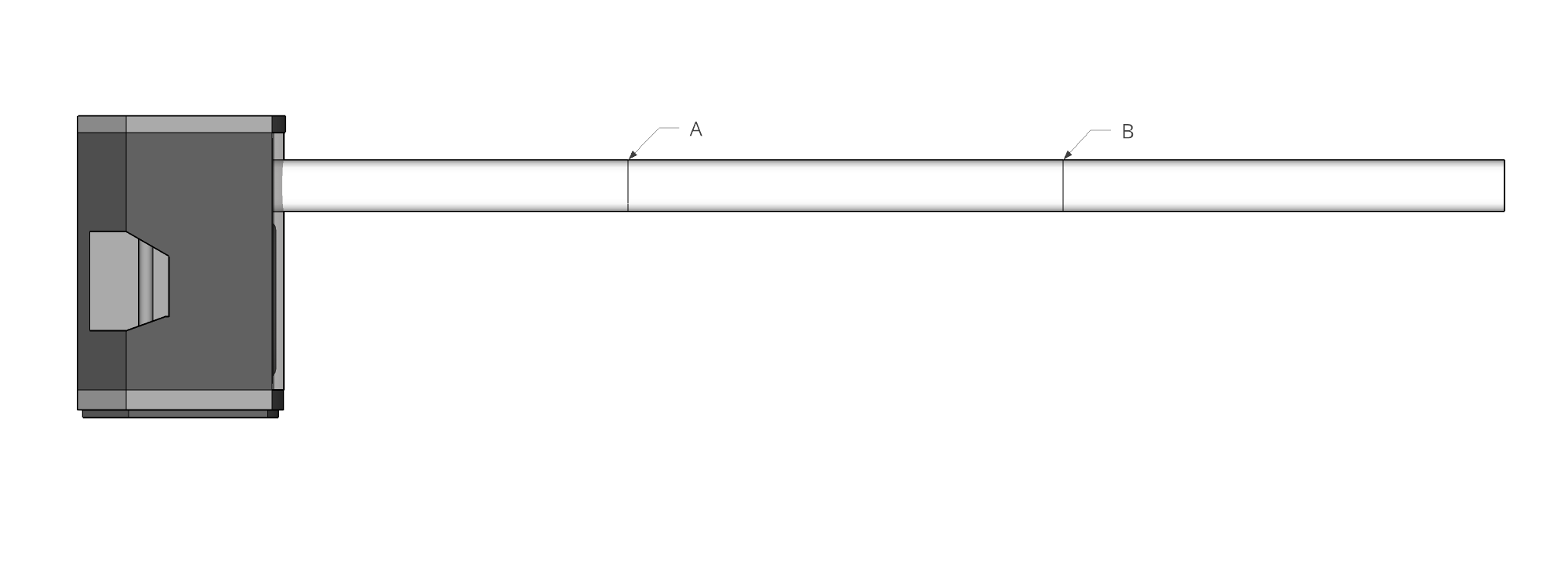

To start with, let’s consider the case where sound is propagating down a narrow tube. In fact, as an approximation we will assume for the sake of the discussion that the tube is infinitely narrow, such that we don’t have to deal with any reflections off the sides of the tube. (This might seem like a strange place to start, but bear with me for a moment.) We could simulate such a scenario by attaching a tube to a loudspeaker, like so:

A more entertaining analogy is the tin can telephone, where the propagation medium is not air, but a piece of string.

In such a setup, the problem is one-dimensional: there is nowhere the sound can go but down the line. Furthermore, since we’ve assumed earlier that the medium is lossless, there really is no reason for any energy to get lost as sound propagates down the tube. Therefore the sound pressure at points A and B (as well as any other point along the tube) is equal. It’s as simple as that.

Two dimensions

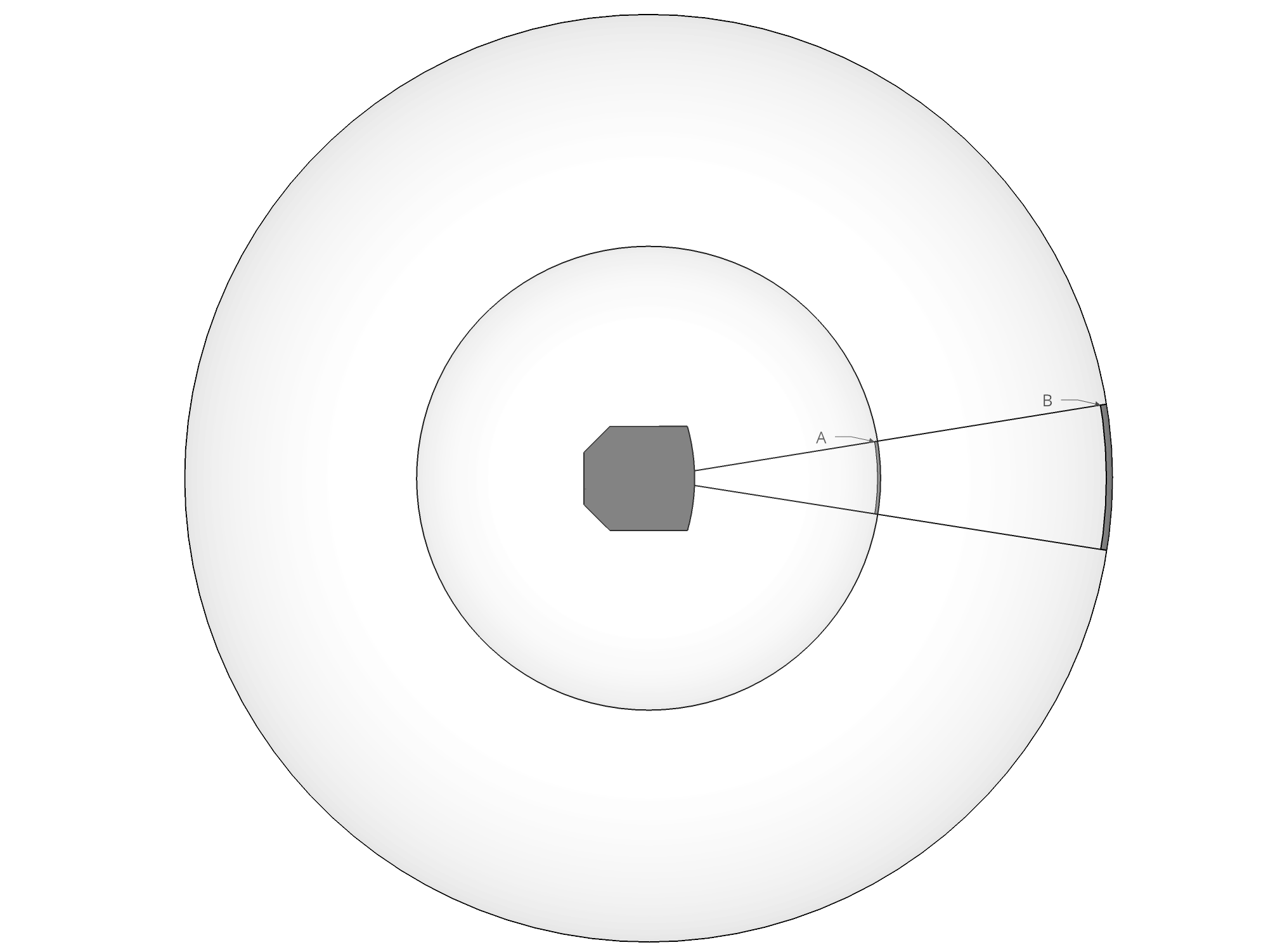

Let’s go one step further and add a second spatial dimension into the mix. One could imagine that our loudspeaker is sandwiched between two parallel planes, where the space between the two planes is infinitesimal:

Another possible analogy is a vibrating piece of paper — a two-dimensional upgrade to the tin can telephone from the previous section.

In this setup things get more complicated, because the loudspeaker is radiating sound in many directions at once. This can be conceptualized as expanding circles called wavefronts. As a wavefront gets farther and farther away from the sound source, its circumference increases. However, energy does not magically appear out of thin air as this happens, so the same amount of sound energy gets spread over a larger circle. In the diagram above, the wavefronts represented by the inner and outer circles carry the same amount of energy in total, but since the outer circle is larger, the sound pressure at a given point on the circle is lower. [note] This reasoning does not require that the source be a monopole, i.e. that it radiates sound equally in all directions. In other words, sound energy is not necessarily evenly distributed along the circle. In general, loudspeakers are not monopole sources; at higher frequencies, they will typically radiate more sound out the front than out the back. Directivity makes no difference as far as this post is concerned, but it is an important concept in other contexts. [end note]

We can easily quantify the rate at which sound pressure decreases as the wavefront gets wider. In the above example, the distance between the source and point A is exactly half the distance to point B. In other words, the radius of the outer circle is double the radius of the inner circle. The circumference of a circle is proportional to its radius, so doubling the radius is equivalent to doubling the circumference. Doubling the circumference means that a given amount of sound power gets spread over twice the area, which in turn means that the sound power per unit area (i.e. the sound intensity) is halved. Sound intensity varies with the square of sound pressure, [note] This is because sound intensity is the product of sound pressure and particle velocity, and particle velocity is proportional to sound pressure. As a result sounds pressure is multiplied with itself. This is analogous to electric power dissipated in a resistor being proportional to the square of voltage. [end note] therefore the ratio of sound pressure between the two circles is the square root of 2, or 3 dB.

This leads us to conclude that, when sound propagates along two spatial dimensions, and keeping in mind the important assumptions we’ve made so far, a doubling of the distance to the sound source results in a 3 dB drop in sound pressure level.

Three dimensions

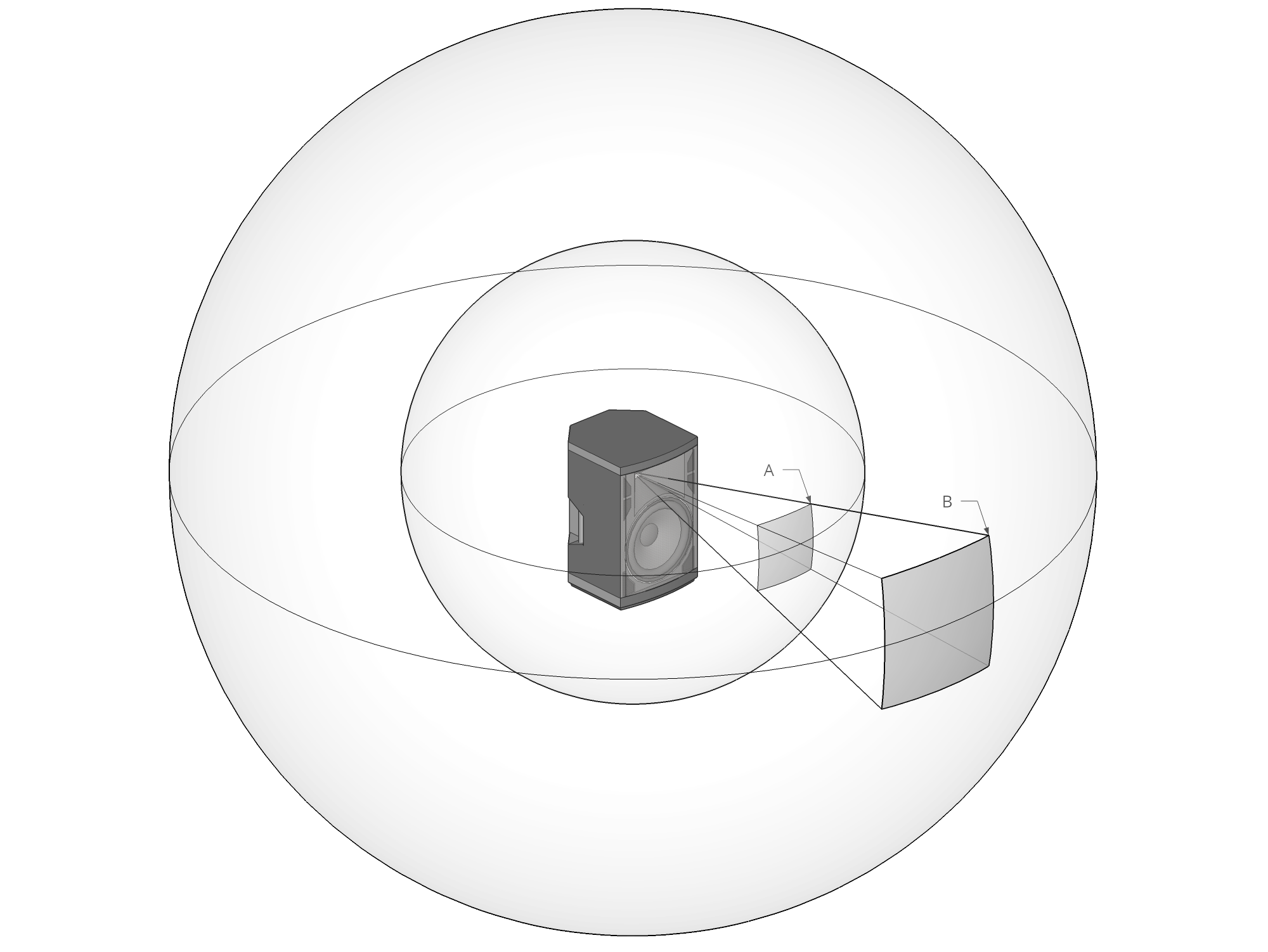

Finally, let’s enter the real world and in its three spatial dimensions. As one would expect, our circles are now spheres:

From this point forward the reasoning is very similar to the two-dimensional case, except this time we’re dealing with surfaces, not lines. The surface of a sphere is proportional to the square of the radius, so doubling the radius is equivalent to quadrupling the surface. Quadrupling the surface means that a given amount of sound power gets spread over an area four times as large, which in turn means the sound intensity is divided by 4. Therefore, the ratio of sound pressure between the two spheres is the square root of 4, which is, well, 2, or 6 dB.

This leads us to conclude that, keeping in mind the important assumptions we’ve made so far, a doubling of the distance to the sound source results in a 6 dB drop in sound pressure level (SPL). This fundamental result, which applies not just to sound waves but to various other physical phenomena, is called the inverse-square law. [note] This is because intensity decreases with the square of the distance. Strictly speaking, since we’re talking about pressure this should be called the inverse-proportional law, but that term is seldom used in practice. [end note] Calculators exist to compute the drop for any arbitrary distance ratio.

Air attenuation

At the beginning of this post, we’ve made the assumption that sound is propagating through a lossless medium. But remember that sound is a pressure wave; by definition, its propagation involves the movement of particles that comprise the medium. In the case of air, that’s mostly oxygen and nitrogen. Because such movement goes against the natural equilibrium of the medium, it requires an expenditure of energy, which is dissipated as heat. As a result, the total energy carried by a sound wave tends to decrease as it travels through the air, in addition to the loss of sound pressure caused by the inverse-square law described in the previous section. [ref] Engineering Acoustics, “Attenuation of sound waves”; Smith, Julius O., Physical Audio Signal Processing, “Air Absorption”. [end ref] [note] Contrary to what some may believe, this doesn’t seem to have anything to do with “loops of energy” that somehow “supply the body with vital life force”, however inspiring that might be. [end note]

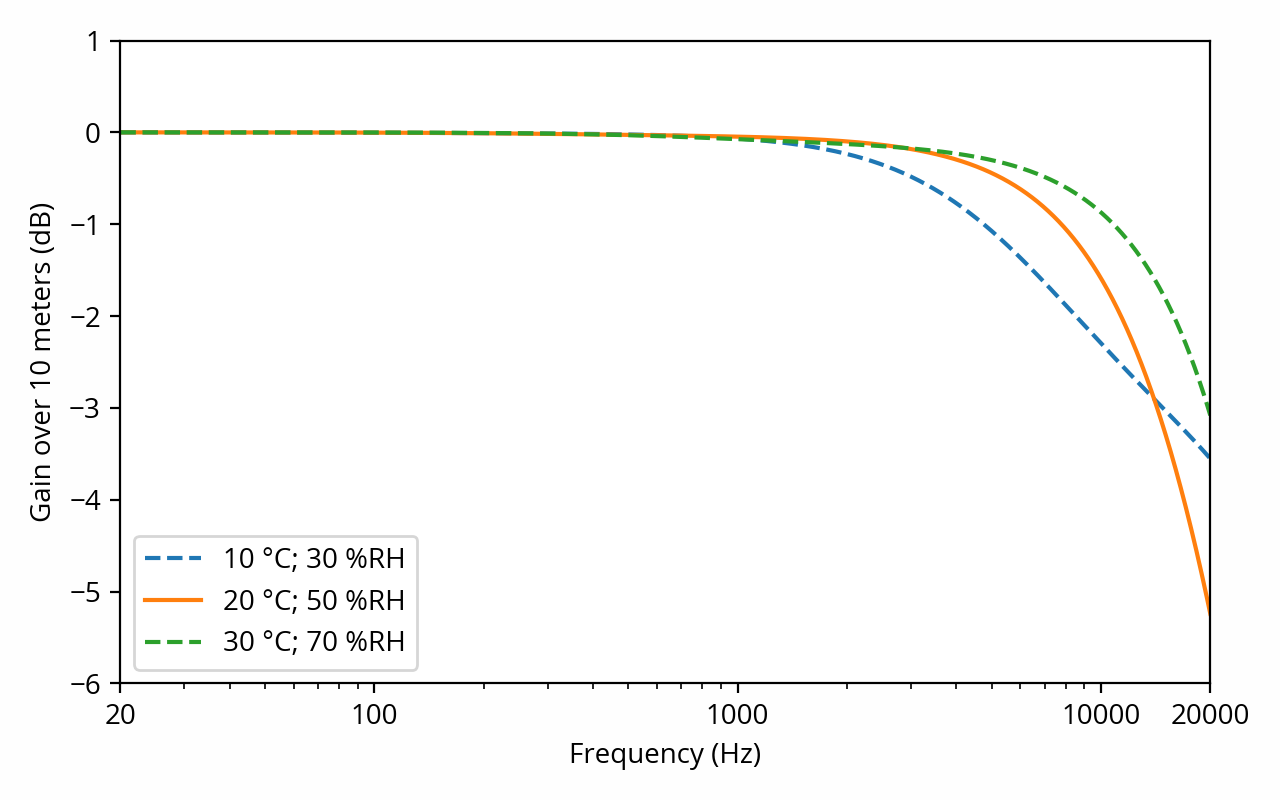

The physical phenomena at play here are non-trivial. The precise amount of sound absorption per unit of distance traveled in air depends on ambient pressure, temperature and humidity, requiring the use of a calculator. Most importantly, it increases with frequency, which means, somewhat shockingly, that air itself exhibits frequency response distortion. Here’s how things look like for various atmospheric conditions: [ref] Calculated according to ISO 9613–1:1993, Acoustics — Attenuation of sound during propagation outdoors — Part 1: Calculation of the absorption of sound by the atmosphere. [end ref]

Immediately, we can observe that below a few kHz, there is not much attenuation to speak of; it is practically negligible at low and medium frequencies. This should dispel the common misconception that attenuation of sound with distance is due to absorption by the air — in reality, that phenomenon is dwarfed by the inverse-square law that we’ve discussed above.

On the other hand, absorption cannot be neglected for high frequencies. In conditions typical of a living room (20 °C, 50% relative humidity), a 10 kHz sound wave will be down ~1.5 dB after 10 meters in addition to the inverse square law and other phenomena. It’s small, but it’s not zero, and it tends to go downhill fast over the last octave of the audible frequency range.